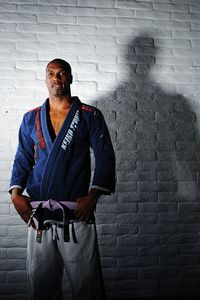

Mark J. Rebilas/US Presswire for ESPN.com

Michael Westbrook is finished with football, but his immense athletic ability is not going to waste.

TEMPE, Ariz. -- It was early evening at Arizona Combat Sports and the man behind the counter had his feet propped on a desk and his hands folded comfortably behind his head. A visitor inquired about the whereabouts of Michael Westbrook. "I'm Michael Westbrook,'' the man said as he stood and offered a handshake and smile. '95 NFL draft • First-round selections

Those are gestures Westbrook couldn't offer with much certainty or happiness a decade ago in the middle of a turbulent NFL career, when outrageous expectations, eggs bouncing off his front door and rumors about his sexual orientation made life miserable.

As Westbrook, 35, began giving a tour of the mixed-martial arts training facility, he was downright gleeful. Funny, but the writer and photographer he guided are members of the media, a group Westbrook collectively despised when he was playing wide receiver for the Washington Redskins and failing to live up to the lofty expectations that came with being the fourth overall pick in the 1995 draft.

He pointed out the rings where guys training for Ultimate Fighting slug each other with very few rules. Westbrook moved through another room full of weights before stopping at the door to the room at the back of the facility. The pause is appropriate because you're about to enter Westbrook's sanctuary. You're about to enter the place where Michael Westbrook truly found Michael Westbrook and forgot football. "I love my life,'' Westbrook said. "I'm having fun.'' The good fight

Life is simple and quiet for Westbrook these days. He lives in nearby Mesa ("I could live in Scottsdale, but it's too fake," he said). When he's not with his daughter and two sons, there are two staples in just about every day. [+] Enlarge

Mark J. Rebilas/US Presswire for ESPN.com

Westbook (top) is pursuing a black belt in Brazilian jujitsu -- and having a lot of fun in the process.

There's a weightlifting session at a health club in the morning. At night, he walks into that back room and becomes exactly what he and the Redskins had hoped for when he was drafted with the No. 4 overall selection out of Colorado. Here at 7:30 on most nights, Westbrook is the best athlete around, excelling with every movement, while totally at peace. In a room that looks like a basketball court without baskets, and a floor covered with blue mats, the guy who came up short of forecasts to be the best wide receiver ever, is well on his way to elite status in Brazilian jujitsu. The sport is similar to wrestling in that it's a ground-based fight, but is far more technical. Westbrook dabbled in martial arts during his football days, but didn't really get into Brazilian jujitsu until his career ended in 2002. He's won national and Pan-Am championships as a blue and purple belt and he hopes to soon become a brown belt. If all goes according to plan, he'll be a black belt -- the highest level in the sport -- within a couple years. Generally, most black belts take eight to 10 years of intense training to reach that level. Westbrook dabbled briefly in Ultimate Fighting, defeating former NFL player Jarrod Bunch in his only bout. [+] Enlarge

Mark J. Rebilas/US Presswire for ESPN.com

Brazilian jujitsu resembles wrestling and is less violent than Ultimate Fighting. "I've never gotten a good feeling from hitting someone in the face,'' Westbrook said.

"I've never gotten a good feeling from hitting someone in the face,'' Westbrook said. "I had to do it growing up to defend myself, but I never liked it. A lot of people get off on that, but I don't want to do it.'' What Westbrook wants to do is roll, that's what participants call Brazilian jujitsu. There's no prize money. That's fine with Westbrook, who lives comfortably off business investments and the money he made playing football. The money, Westbrook said, is the only good thing to come out of his career. Jujitsu is Westbrook's passion. Football was his pain. "This is a lot easier and a lot more fun,'' Westbrook said. "I don't have to worry about coaches and it's not nearly as dangerous. I don't have to worry about pleasing the public and the announcers. Or getting eggs thrown at my door because I dropped a ball. I don't have to worry about any of that.'' Few fond football memories

These days, Westbrook will tell you he hates football and, aside from the big scar on his left knee, there are no visible reminders of his career. "If you walked into my house, you'd never know I played football,'' Westbrook said. "There are no game balls or pictures or anything like that. I sent all that stuff to my mom. There's no football stuff left in my house.'' Or in his heart.

"I didn't like the lifestyle,'' Westbrook said. "I didn't like the guys. I didn't like living like that. Everybody was fake and thought they were something they weren't. A lot of guys weren't good people and I just couldn't live like that.'' [+] Enlarge

Al Bello/Getty Images

Westbrook had his moments with the Redskins, but he never realized his vast potential in the NFL.

Westbrook walked away from the game after one last dismal season with the Cincinnati Bengals in 2002. "I could still jump over 40 inches, still run the 40 in about 4.3 and still bench press 400 pounds,'' Westbrook said. "I still had my physical skills. But mentally -- mentally -- the game made me toast.'' Toast was what Westbrook was supposed to make of NFL defensive backs when the Redskins drafted him. He was 6-foot-4 and 230 pounds with a knack for making big plays, including the "Miracle in Michigan,'' where he caught a bomb from Kordell Stewart to give Colorado a last-second victory against Michigan in 1994. But all the promise and expectations never translated into success. "Ah, Michael, that's unfortunate,'' said Norv Turner, the coach of the Redskins through most of Westbrook's tenure. "Michael had all the skills in the world and he worked hard. I don't know how to explain what happened other than to say he had bad luck.'' Bad luck with injuries and two very public outbursts are Westbrook's legacy. But there was that 1999 season, when Westbrook flashed signs of what could have been. After nagging injuries prevented him from catching more than 44 passes in any of his first four seasons, Westbrook played a full 16-game season for the first time. Although five of those games were played with a cast on his broken hand, Westbrook caught 65 passes for 1,191 yards and nine touchdowns. "In 1999, that was him. That was Michael Westbrook,'' said Charlie Casserly, Washington's general manager when the Redskins drafted Westbrook. "That's what we hoped every year would be like.'' There was sudden hope that Westbrook had turned a corner and the troubled early days would be forgotten. That didn't happen. Two games into the 2000 season, Westbrook tore up his knee. He returned in 2001, but the long-standing feud with the media and fans had reached a crescendo that led him to Cincinnati and retirement. Wounded prideWestbrook says he believes the injuries came because he was too aggressive, trying too hard to make impossible catches in practice. "I was a stunt man as a wide receiver,'' he said. But Westbrook will be the first to tell you the reason for his disappointing career wasn't all the result of injuries. It's more than a little ironic that the guy who doesn't like to hit people in the face is best known for beating the heck out of teammate Stephen Davis in practice.

The video clips were all over the national news and Westbrook said the incident left a lot of people with the false impression that he was a homosexual. Westbrook said the details have been misreported for more than a decade. [+] Enlarge

Mark J. Rebilas/US Presswire for ESPN.com

Fully content with his current situation, Westbrook rarely feels the need to reflect upon the highs and lows of his football career.

"He didn't call me a name,'' Westbrook said of Davis. "That's where it gets mixed up. It got reported and it got changed into something monstrous. I was talking to him, Brian Mitchell and Terry Allen. They were talking about 'letting us handle the team.' I was like, 'You all are a bunch of jealous [f----]. You all are just jealous of everything I have.'"Stephen Davis told me I needed to shut up and all that stuff I was saying sounded like some gay [s---], like I'm soft, not like I'm gay. That's all he said. It wasn't like, 'You're gay,' but it got changed to that really quick. So the connotation is Michael Westbrook is gay.''

The connotation has faded, but not completely. "My ex-girlfriend heard it about a year ago from this guy and she went nuts,'' Westbrook said. "Everybody that knows me knows that's the farthest thing from the truth. For about three years, I wanted to lock myself in the house and never come out.''

Davis, who is retired, was not available for comment and has rarely talked about the incident through the years. Westbrook said he and Davis eventually became friendly and remain on good terms.

That incident with Davis wasn't the only reason Westbrook led a hermit-like existence through much of his time in Washington. His other claim to infamy came in an overtime game against the New York Giants late in the 1997 season. On one play, Westbrook said a linebacker stuck his hand through his facemask and poked him in the eye. He left the game momentarily. On the next play back, he thought he made a catch near the sidelines. Three referees huddled and decided he was bobbling the ball as he went out of bounds. Westbrook took off his helmet and slammed it to the ground. He was penalized 15 yards and the Redskins were backed up out of field-goal range. The game ended in a tie and the Redskins finished the season 8-7-1 and out of the playoffs. If they had won, they would have been in the playoffs. If one play summarized Westbrook's career, that was it. "I was so young and passionate and wanting to win and please the coaches and the fans,'' Westbrook said. "I wanted to please everybody and I was forgetting about myself. The one thing that mattered most was completely put on the back burner for years. I never cared about myself. That's probably what hurt me most. If I had tried to please myself and thought about myself and hadn't acted that way, I'd be a lot better off.'' Where he belongs

As the excitement builds among football fans for another draft, Westbrook feels sorrow for the prospects. He knows some will end up like him and never live up to the expectations. "You get drafted that high and everybody's going to point a finger at you,'' Westbrook said. "I brought a lot of it on myself with some of my actions. If I had been a good boy and I was scoring touchdowns and we were winning, nobody would have noticed the helmet or the fight. I didn't accomplish much because, in their eyes, I was just a rich kid who was crying. I just wanted to play ball and be that all-world receiver that everyone thought I should be and that I knew that I was.'' Maybe that's why Westbrook has found solace in Brazilian jujitsu. Out on the mat, it's just him and an opponent. There are no screaming coaches and fans. There are no expectations other than his inner drive to succeed. "I didn't love the glory part of football,'' Westbrook said. "That's not me. All I wanted to do was go play football and score a touchdown. I couldn't stand the fans and media getting on me when we were losing.'' Aside from occasional family and friends at his competitions, Westbrook's on his own on the mat. That's the way he likes it. It took a long time to realize, but Westbrook said he wasn't cut out for team sports. He's a loner, who finally has found his true calling. "I never even think about football now,'' Westbrook said. "I know that's weird. But the thing about it was I wasn't a football player, I was an athlete. Here, I'm an athlete with no one else to worry about.''